The demands of India’s fledgling agritech industry are as varied as their challenges. Given the complexity of the industry in terms of geographies, local ecosystems, dependence on monsoons, and a host of varying and often changing factors, it’s not a surprise. Also, agriculture is a state subject. “The most important thing is the execution, which is an outcome of better synchronisation between the Central government and state governments. Otherwise, the Budget and policies remain on a piece of paper,” says Shashank Kumar, Co-founder and CEO of DeHaat, a startup that provides full-stack agricultural services to farmers. Given that the term “agritech” was mentioned for the first time in the previous year’s Budget, the sector is happy to be recognised as an important category. However, the reigning opinion is that a lot needs to be done on-ground to make it easier for agritech startups to operate, given the complexity of factors they deal with everyday.

The government pegs the number of agritech startups in India at over 2,000, up from 80-100 eight years ago. According to a report by AgFunder and Omnivore, both foodtech and agritech venture capital firms, investments in agrifood-tech startups increased 119% to $4.6 billion in financial year 2021-2022.

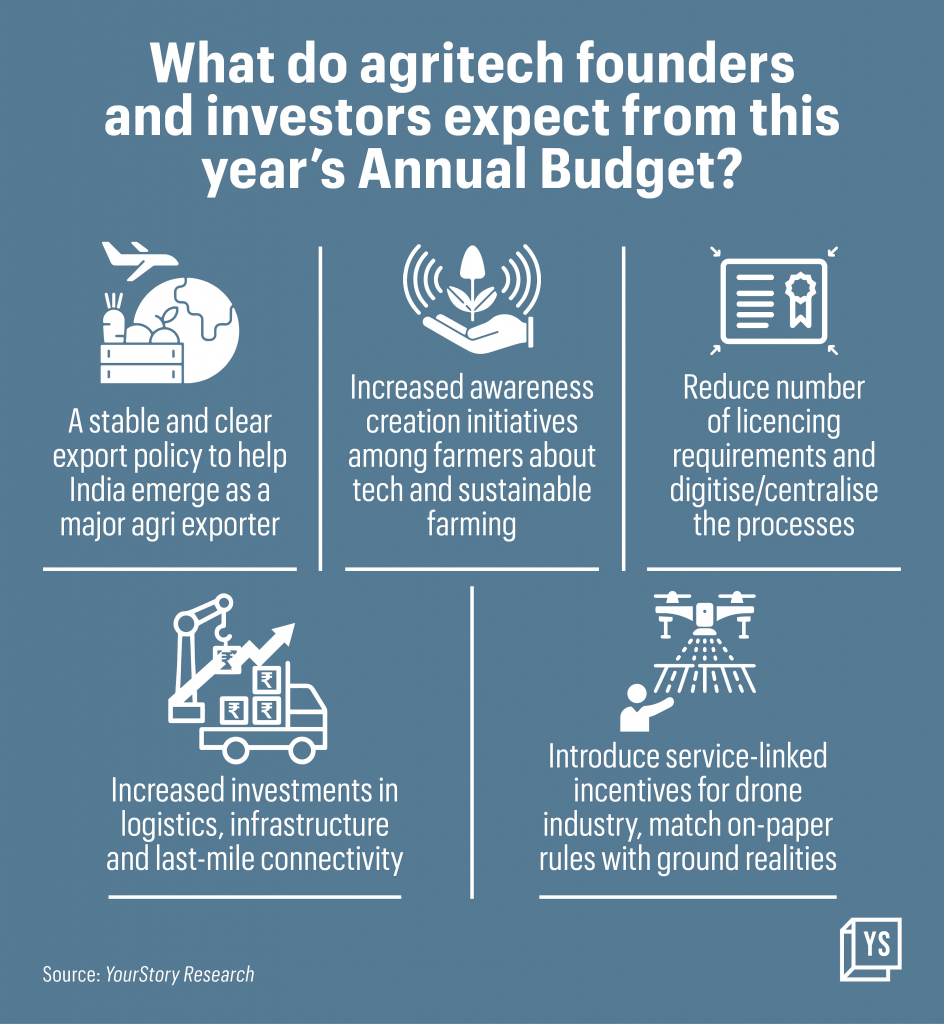

A stable export policy

India crossed the $50-billion milestone in exports of agricultural products in FY22, the highest ever, according to the Union commerce ministry. Some founders and investors say there’s a need for a stable policy for agricultural exports, communicated in advance to ensure better planning. “This idea that you constantly stop exports whenever prices start to go up prevents India from becoming a dominant agricultural exporter,” says Mark Kahn, Managing Partner at Omnivore, an agri-focused venture capital firm.

“There should be funding to facilitate agricultural export capex, and an agricultural export policy that says we will export even if prices (of certain commodities) go up.” India bans exports of certain commodities whenever prices rise to rein in food inflation, but, on the other hand, exports shield farmers from low domestic commodity prices. Tauseef Khan, Co-founder and CEO of Gramophone, a full-stack intelligent farming platform, says better clarity on exports of commodities such as wheat and onion would help. “A clearer policy for the next one year on how much exports would be allowed and what would be the level of procurement by the government—from planning and trading perspectives—is needed. If there are price benefits, those will trickle down to the farmers,” he says. A crop-specific, freight subsidy approach would help India continue upward on the exports trajectory, says Shashank Kumar of DeHaat, which offers end-to-end agricultural solutions to Indian farmers. He suggests that remote or land-locked states that are core agricultural players be offered incentives to start trade with new destinations, instead of just relying on places with good port connectivity to be major export hubs. Incentives for key stakeholders such as agri-businesses and logistics companies would enable new source and export destinations to be linked.

Digitisation of processes

The complexity of running an agritech business cannot be emphasised enough. Krishify’s Rajesh says that some agricultural processes are still ancient, and even if local officials want to give the green flag, they are unable to because they are either very lengthy or unclear. “Agri is something where there are a lot of government policies and regulations; a lot of licences are required. I think the government is also in the process of figuring out how to collaborate with startups. So, though communication between the two has started, we are yet to come up with a lot of actionable items,” he says. Digitisation of processes can help the government and the companies to do free trade, Tauseef believes. Giving an example from the perspective of agricultural input, he says companies need to renew their licences annually, which is still an offline process. “Though digitisation has started happening in agriculture, there needs to be a concerted effort in digitising the operational value chain, which can unlock the ease of doing business for companies like ours and even the traditional ones,” Tauseef explains. DeHaat’s Shashnk explains that when licensing mechanisms were designed, the assumption was that those who applied for licences for both input (seeds, fertilisers, etc.) and output (crops) would operate at the village, block, or the most district level. This led to the independent designing of licensing requirements in each district. “What that means today is that, let’s say, if someone like DeHaat or any other agritech company has to work on the input and output sides in 10 districts, they will have to apply for a total of 10X2 (20) licences. “Even within the input, they need licences for seeds, fertilisers, and pesticides. This means three licences for each district (10X3 = 30). And then again, on the output side, one licence for dry (crop), and another for fruits and vegetables means two (licences). So, a total of 50 licences,” Shashank says. He adds that a single-window clearance at the state level should do the trick.

More focus on logistics and infrastructure

Rajesh of Krishify has first-hand experience with how the state of rural logistics can impact an agritech business. His startup recently transitioned from being a community to a community-led ecommerce model. He says that about 30% of the orders generated on their platform do not get fulfilled because none of the logistics players can service some areas. “Farmers are in dire need of getting the right products (farm inputs) at the right time. These are highly essential; their livelihood depends on them. No matter the efforts you put into it, you’re unable to send them these products in less than five days,” Rajesh says. The Indian Postal service has the maximum coverage in the country but needs a revamp, he adds. The average time it takes for orders on Krishify’s platform to reach farmers is around 5-6 days; the maximum time it takes is around two weeks. Rajesh says the supply chain is an issue on the output side as well. “When I talk to agritech founders in that segment, they say fruits and vegetables are very difficult to manage as they are highly perishable. A few hours of delay can result in up to 60% of loss in revenues,” he says. Apart from providing and strengthening market linkages, especially for perishable commodities, there need to be government initiatives that focus on building cold storage facilities at the source. This can help farmers design distribution plans based on shelf life and other factors related to the vegetables and fruits they grow. The government launched the Agriculture Infra Fund (AIF) in July 2020 “for creation of post-harvest management infrastructure and community farm assets, with benefits, including 3% interest subvention and credit guarantee support”. Omnivore’s Mark says the government has facilitated “quite a bit of processing grids for infrastructure” and that “they should continue doing that”.

SOURCE: YourStory.com

Leave a Reply